Derek Yach觀點》公共衛生的原罪:疫苗、電子菸與信賴之戰

公共衛生建立在信任之上——也會因背叛而粉碎。當家長懷疑疫苗、當吸菸者質疑較安全的代用品時,科學之所以踉蹌,往往不是因為證據本身,而是因為人們選擇相信什麼。兩個錯誤資訊的「原罪」解釋了我們為何走到今天:一篇關於疫苗的詐欺研究,與菸草產業長達數十年的否認。這兩件事,至今陰魂不散。

1998 年,英國醫師安德魯・魏克菲爾德(Andrew Wakefield)在《刺胳針》(The Lancet)發表研究,聲稱麻疹、腮腺炎、德國麻疹(MMR)疫苗與自閉症有關。那份數據遭到操弄、方法不當,論文後來被撤稿,魏克菲爾德也被吊銷醫師執照。但謊言仍然存活。對渴望解答的家長、對急於證明「菁英不可信」的陰謀論者、以及把懷疑當武器的政治人物而言,這個主張彷彿成了福音。

那場單一的造假,擴散成一場運動。社群媒體如同在星火上澆了汽油,形成一個個部落,使「拒打疫苗」不僅是醫療選擇,更成為一種文化認同。即便到了 COVID-19 疫情期間,面對壓倒性的證據,拒打疫苗的比例依然頑強。魏克菲爾德這位身敗名裂的醫師或許會被遺忘,但他釋放出的不信任,卻揮之不去。

菸草的故事更糟——因為這個原罪來自企業。從 1950 年代起,壓倒性的科學證據顯示吸菸會致命。然而數十年來,菸商資助假研究、否認顯而易見的事實,並不斷遊說拖延管制。1994 年,七家菸草公司執行長在美國國會作證時發誓——這是謊言——他們不相信尼古丁會讓人上癮。內部文件後來證明,他們早就心知肚明。

代價是什麼?數以百萬計本可避免的死亡,以及一次深刻到被寫進全球條約法的公共衛生背叛。世界衛生組織《菸草控制框架公約》(FCTC)第 5.3 條宣示,菸草公司的利益與公共衛生「不可調和」,要求政府與研究社群遠離其干預。若說魏克菲爾德是自毀名節,那麼大菸草則是徹底汙染了這口井。

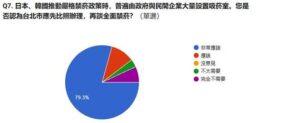

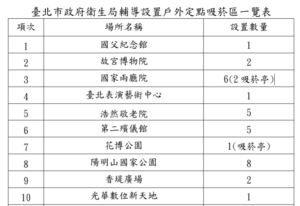

然而,數十年過去,我們又在爭論另一個尼古丁議題:電子菸。越來越多證據顯示,電子菸遠較紙菸危害低,並能幫助戒煙。可仍有許多人——決策者、家長,甚至醫師——相信相反的說法。為什麼?因為由像彭博(Bloomberg)這類慈善基金會資助的行動者、非政府組織與國際衛生團體,不斷投下質疑,重複宣稱「尼古丁會致癌」或「電子菸和紙菸一樣糟」。這些不是誇大,就是赤裸裸的謬誤;它們在各自的回音室裡被放大,就像反疫苗迷思被放大的方式一樣。

於是出現了奇特的對稱:一邊是流氓醫師的欺騙,在陰謀論包圍下威脅疫苗接種;另一邊是企業遺留的欺瞞,使數以百萬計的吸菸者即便有更安全的替代品,仍被鎖在可燃紙菸上。

問題相同:那些造成原罪的人,還能幫忙修補傷害嗎?

對疫苗來說,答案很簡單。我們不需要安德魯・魏克菲爾德懺悔。體制可以透過心理學家范德林登(Sander van der Linden)所稱的「預先揭穿」(prebunking)來修復信任:讓人們先以小劑量接觸錯誤資訊,同時教他們為何那是錯的,幾乎就像替「謊言」打預防針。證據顯示,這確實能幫助人們抵抗陰謀論。罪人已遠去,但修正可以持續。

對菸草而言,答案更複雜。罪人仍在場。曾經對尼古丁說謊的同一個產業,現在宣稱自己致力於「減害」。支持電子菸相對安全性的科學證據愈來愈強,但一旦研究上印著菸商的商標,許多人就不再願意傾聽——這也無可厚非。

但公共衛生不能靠把這個產業想像成不存在。它握有資源、科學家與數據;若導流得當,足以加速減害。關鍵在於「獨立性」。想像一個近似「真相與和解」的機制:資金部分來自產業,但完全由受尊敬的公部門科學家主導,並交由像 Wellcome Trust(惠康信託基金會)等機構監督。公司可以提供證據,但避免在公共場域替自己辯護,因為只要他們一介入,懷疑就會升高。

沒有信任,疫苗與電子菸都無法兌現其救命的承諾。當家長害怕自閉症時,疫苗施打就停滯;當吸菸者害怕轉換時,他們就繼續抽紙菸。兩種情況下,錯誤資訊都在回音室裡滋長,並讓社群更加極化。

這兩段歷史告訴我們:一旦信任破裂,光靠事實不足以修復。還需要謙卑、透明,以及足以把真相與宣傳區隔開來的制度。魏克菲爾德的謊言引爆了一場文化戰爭;大菸草的謊言則讓整個產業被永久放逐。要向前走,我們必須更擅長把公共衛生與不良行為者隔離,同時用務實的方法修正錯誤資訊——不論它來自他們,還是來自他們的反對者。

因為現實是:安全的疫苗與較安全的尼古丁產品,是預防過早死亡最有力的工具之一。讓錯誤資訊——無論新舊、來自企業或陰謀——削弱它們的影響,絕不只是失誤而已;那才是更大的罪。

原文章來源:https://derekyach.substack.com/p/the-original-sins-of-public-health

The Original Sins of Public Health: Vaccines, Vapes, and the Battle for Trust

Public health is built on trust—and shattered by its betrayal. When parents doubt vaccines or smokers question safer alternatives, science stumbles not because of what evidence shows, but because of what people believe. Two “original sins” of misinformation explain how we got here: a fraudulent vaccine study and Big Tobacco’s decades of denial. Both still haunt us.

In 1998, a British doctor named Andrew Wakefield published a study in The Lancet claiming the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine was linked to autism. The data were manipulated, the methods corrupt, the study later retracted. Wakefield lost his medical license. But the lie endured. For parents desperate for explanations, for conspiracy theorists eager for proof that elites could not be trusted, and for politicians weaponizing skepticism, the claim became gospel.

That single fraud metastasized into a movement. Social media poured gasoline on the sparks, creating tribes where rejecting vaccines became not just a medical decision but a cultural identity. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, in the face of overwhelming evidence, vaccine refusal remained stubbornly high. Wakefield, a disgraced doctor, could be forgotten. But the mistrust he unleashed cannot.

The tobacco story was worse—because this original sin was corporate. From the 1950s onward, overwhelming science showed smoking killed. Yet for decades, cigarette companies funded sham studies, denied the obvious and lobbied relentlessly to delay regulation. In 1994, seven chief executives stood before Congress and swore—falsely—that they did not believe nicotine was addictive. Internal documents later showed they knew the truth all along.

The cost? Millions of preventable deaths and a public health betrayal so profound that it became immortalized in global treaty law. Article 5.3 of the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control declared tobacco companies’ interests “irreconcilable with public health,” prohibiting governments and researchers from engaging with them. If Wakefield poisoned his reputation, Big Tobacco poisoned the well forever.

And yet, here we are, decades later, debating another nicotine issue: vaping. Evidence grows that e-cigarettes are far less harmful than smoking and can help people quit. Yet many people—policymakers, parents, even doctors—believe the opposite. Why? Because activists, NGOs and international health groups funded by philanthropies like Bloomberg have relentlessly cast doubt, repeating claims that nicotine causes cancer or that vaping is just as bad as smoking. These are exaggerations or outright falsehoods, amplified in their own echo chambers, just as anti-vaccine myths are in theirs.

Which leaves us with a strange symmetry. In one case, a rogue physician’s deception surrounded by conspiracy theorists threatened vaccine uptake. In the other, a legacy of corporate deceit keeps millions of smokers chained to combustible cigarettes even when safer alternatives exist.

The question is the same: Can those responsible for the original sin ever help correct the damage?

For vaccines, the answer is simple. We don’t need Andrew Wakefield to repent. Institutions can repair trust by doing what psychologists like Sander van der Linden call “prebunking”: exposing people to misinformation in small doses while teaching them why it is false, almost like a vaccine against lies. Evidence shows this helps people resist conspiracy theories. The sinner is gone; the correction goes on.

For tobacco, the answer is more complicated. The sinner is still here. The same industry that lied about nicotine now claims it is committed to harm reduction. The science on vaping’s relative safety grows stronger—but when it comes stamped with the logos of cigarette companies, many stop listening. And who could blame them?

But public health cannot simply wish the industry away. It has the resources, scientists and data that could accelerate harm reduction, if channeled correctly. What’s needed is independence. Imagine a process akin to truth and reconciliation: funded partly by industry but led entirely by respected, public-sector scientists and overseen by foundations like the Wellcome Trust. Companies could provide evidence but refrain from defending themselves publicly, where their very involvement breeds more suspicion.

Neither vaccines nor vapes can fulfill their life-saving promise without trust. Vaccines stall when parents fear autism. Smokers keep smoking when they fear switching. In both cases, misinformation thrives in echo chambers and polarizes communities.

What these twin histories show is that once trust is broken, facts alone cannot repair it. It takes humility, transparency and structures strong enough to separate truth from propaganda. Wakefield’s lie created a culture war. Big Tobacco’s lies left an entire industry in permanent exile. To move forward, we must do better at insulating public health from bad actors—while finding pragmatic ways to correct misinformation whether it comes from them or from their critics.

Because here’s the reality: safe vaccines and safer nicotine products stand among the most powerful tools to prevent premature death. Allowing misinformation—old or new, corporate or conspiratorial—to blunt their impact is not just a mistake. It’s the greater sin.